Sacramento-area mom: I know how to save your child from dying of fentanyl as mine did

I know what it is to feel powerless against a problem that seems too big to solve. When I lost my son to a fentanyl overdose, I felt small and alone. I see my son in small, beautiful moments:

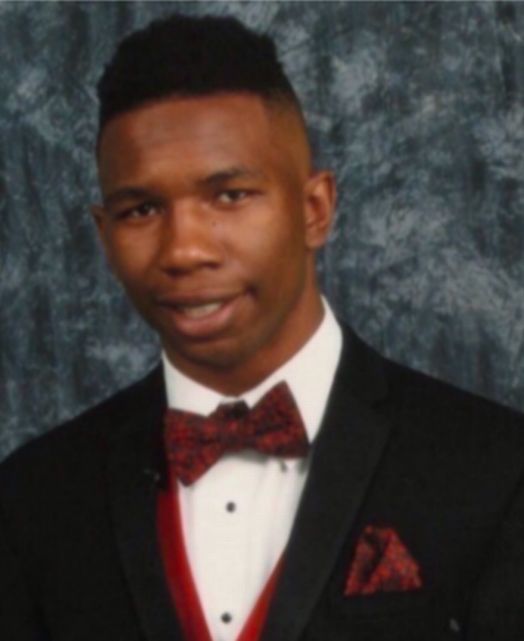

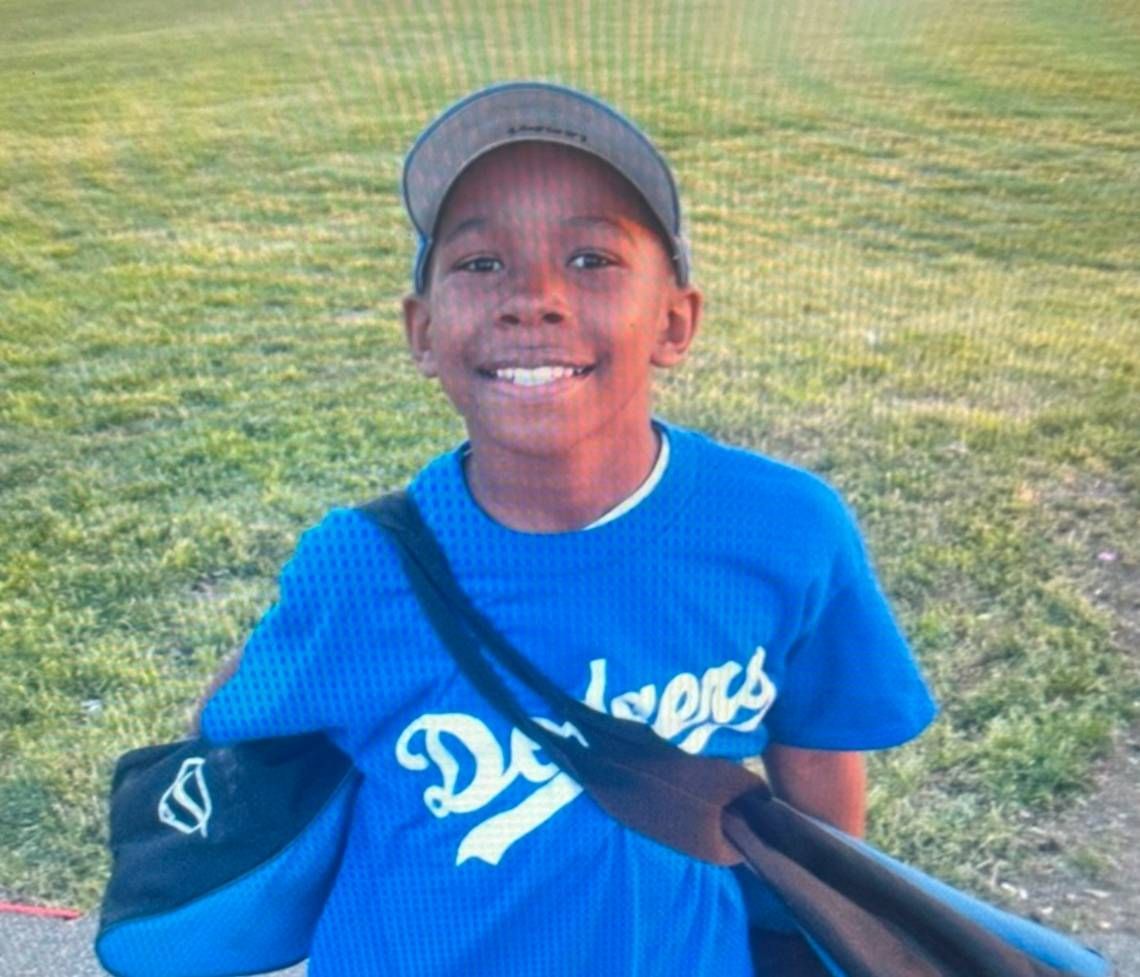

I see him in the morning sun shining through my window; I hear him in a chat with a kind stranger at a coffee shop; I feel his spirit smile when I find forgotten money in a pocket. In the five years since my son, Lamont, died from an accidental fentanyl overdose on his 19th birthday in Rancho Cordova, all I have of him are these bright moments and my own memories.

Since my son’s death, I have committed myself to spreading the word about the dangers of fentanyl and making sure people have information about naloxone, a medicine that can treat and reverse an opioid overdose and is among other resources that can save lives. That’s why I started the Lamont Meyers Foundation and why I have worked every day for the last three years in service of this mission.

February is Black History Month, a time to honor the strides our community has made and our ongoing fight for a better future. February also marks Lamont’s birthday and the anniversary of his passing. My wish this month is that Californians dedicate ourselves to keeping each other and our children safe from fentanyl.

According to the California Department of Public Health’s overdose surveillance dashboard, drug overdoses were a leading cause of death among 18- to 54-year-olds in California between 2020 to 2022.

Fentanyl is at the center of a deadly crisis in our state and our nation and its not going away. Fentanyl can hide in plain sight, and just a small amount can be deadly. My son had no idea there was fentanyl in a pill he thought was a Percocet. I still don’t know where Lamont got the pill — perhaps it was a gift from a friend for his birthday.

In almost 40% of opioid and stimulant overdose deaths — including Lamont’s — a bystander was present. By carrying naloxone, we can potentially save lives and empower bystanders to help prevent overdose deaths. We should all carry this life-saving medicine and learn how to use it.

Naloxone is easy to use, affordable and available over-the-counter at pharmacies — or available for free through community organizations like mine. Naloxone is our strongest ally in the fight against fentanyl, which is why I include it in the emergency kits I distribute across Sacramento and the Bay Area.

When Lamont first passed away, I was embarrassed to talk about it. I felt uncomfortable sharing my story. Now, using my voice is at the center of everything I do. Outreach is one of the primary aims of the Lamont Meyers Foundation. I travel across the state to schools, parks and community centers to pass out emergency kits and talk to people about the dangers of fentanyl and preventing overdoses. Initiating these conversations has helped me cope with my loss and find my strength — and, potentially, helped save lives.

However, one of the biggest challenges to combating fentanyl overdose is stigma, especially in the Black community. We must reduce the stigma attached to carrying naloxone and be willing to reach out and ask for help for a substance use disorder. There are resources, including naloxone, available in our communities, but we cannot be afraid to ask for help. At the Facts Fight Fentanyl website, you can find the information you need to keep yourself and your loved ones safe.

I know what it means to feel helpless and powerless. But the truth is, none of us are: We have the tools and information we need to save lives.